SQLite: Past, Present, and Future

SQLite is the most widely deployed database engine (or likely even software of any type) in existence. It is found in nearly every smartphone (iOS and Android), computer, web browser, television, and automobile. There are likely over one trillion SQLite databases in active use. (If you are on a Mac laptop, you can open a terminal, type "sqlite3", and start conversing with the SQLite database engine using SQL.)

SQLite is a single node and (mostly) single threaded online transaction processing (OLTP) database. It has an in-process/embbedded design, and a standalone (no dependencies) codebase ...a single C library consisting of 150K lines of code. With all features enabled, the compiled library size can be less than 750 KiB. Yet, SQLite can support tens of thousands of transactions per second. Due to its reliability, SQLite is used in mission-critical applications such as flight software. There are over 600 lines of test code for every line of code in SQLite. SQLite is truly the little database engine that could.

|

| The concept art in this blog post are creations of Stable Diffusion. |

This paper, which appeared in VLDB'22 a couple weeks ago, delves into analytical data processing on SQLite, identifying key bottlenecks and implementing suitable solutions. As a result of the optimizations implemented, SQLite is now up to 4.2X faster on the Star Schema Benchmark (SSB). This is a sweet little paper (befitting SQLite's fame). It is technically easy to read yet very fulfilling.

The paper also has an important theme. Throughout the paper, we see time and again how SQLite benefits from its informative profiling utilities and aggressive testing to identify and implement optimizations quickly. Performance and correctness monitoring is a prime factor in development velocity. The ease of profiling SQLite's execution engine enabled the team to pinpoint which virtual instructions were responsible for the bottlenecks, and also to watchout for performance regression issues. Their extensive test suite (consisting of fuzz, boundary value, regression, I/O, out-of mem testing) allowed them to quickly integrate the optimizations into a release build without worrying of breaking other components of the library.

SQLite Architecture

SQLite is embedded in the host application process: instead of communicating with a database server across process boundaries, applications use SQLite by calling SQLite library functions. Not only is this convenient and good for performance, it also shields the user from a lot of distributed systems concerns (stemming from uncertainty of network communication and asymmetry of information) by achieving fate-sharing between the database and the application.SQLite has a modular design. The core modules are responsible for ingesting and executing SQL statements. The SQL compiler modules translate a SQL statement into a bytecode program that can be executed by the virtual machine. The backend modules facilitate access to the database pages and interact with the OS to persist data. Accessory modules include a large suite of tests and utilities for memory allocation, etc.

SQLite’s execution engine, included in the core modules, is structured as a virtual machine. This virtual database engine (VDBE) is the heart of SQLite as it executes the logic of the bytecode program produced by the code generator. (Each SQL statement can be thought of as an executable program.)

VDBE interacts heavily with the B-tree module. An SQLite database file is essentially a collection of B-trees. A B-tree is either a table B-tree or an index B-tree. Table B-trees always use a 64-bit signed integer key and store data in the leaves. Each table in the database schema is represented by a table B-tree. The key of a table B-tree is the implicit rowid column of the table. Index B-trees use arbitrary keys and store no data at all.

The page cache is responsible for providing pages of data requested by B-tree module. The page cache is also responsible for ensuring modified pages are flushed to stable storage safely and efficiently. SQLite uses an abstract object called the virtual file system (VFS) to provide portability across operating systems.

Transactions

SQLite provides ACID transactions with serializable isolation. It has two primary modes: rollback mode and write-ahead log mode.In rollback mode, SQLite begins a transaction by acquiring a shared lock on the database file. After the shared lock is acquired, pages may be read from the database at will.

- If the transaction involves changes to the database, SQLite upgrades the read lock to a reserved lock, which blocks other writers but allows readers to continue.

- Before making any changes, SQLite also creates a rollback journal file. For each page to be modified, SQLite writes its original content to the rollback journal and keeps the updated pages in user space.

- When SQLite is instructed to commit the transaction, it flushes the rollback journal to stable storage.

- Then, SQLite acquires an exclusive lock on the database file, which blocks both readers and writers, and applies its changes.

- The updated database pages are then flushed to stable storage. The rollback journal is then invalidated via deleting in DELETE mode, or truncating in TRUNCATE mode.

- Finally, SQLite releases the exclusive lock on the database file.

- When SQLite needs a page, it searches the WAL for the most recent version of that page prior to the end mark. If the page is not in the WAL, SQLite retrieves the page from the database file.

- Changes are merely appended to the end of the WAL. A commit that causes the WAL to grow beyond a specified size will trigger a checkpoint, in which updated pages in the WAL are written back to the database file.

- The WAL file is not deleted after a checkpoint; instead, transactions overwrite the file, starting from the beginning.

The WAL mode gives faux multiversion-concurrency-control(MVCC) to SQLite. It offers increased concurrency as readers can continue operating on the database while changes are being committed into the WAL. While there can only be one writer at a time, readers can proceed concurrently with the one writer. WAL is also significantly faster as it requires fewer writes to stable storage, and the writes that do occur are more sequential.

Evaluation

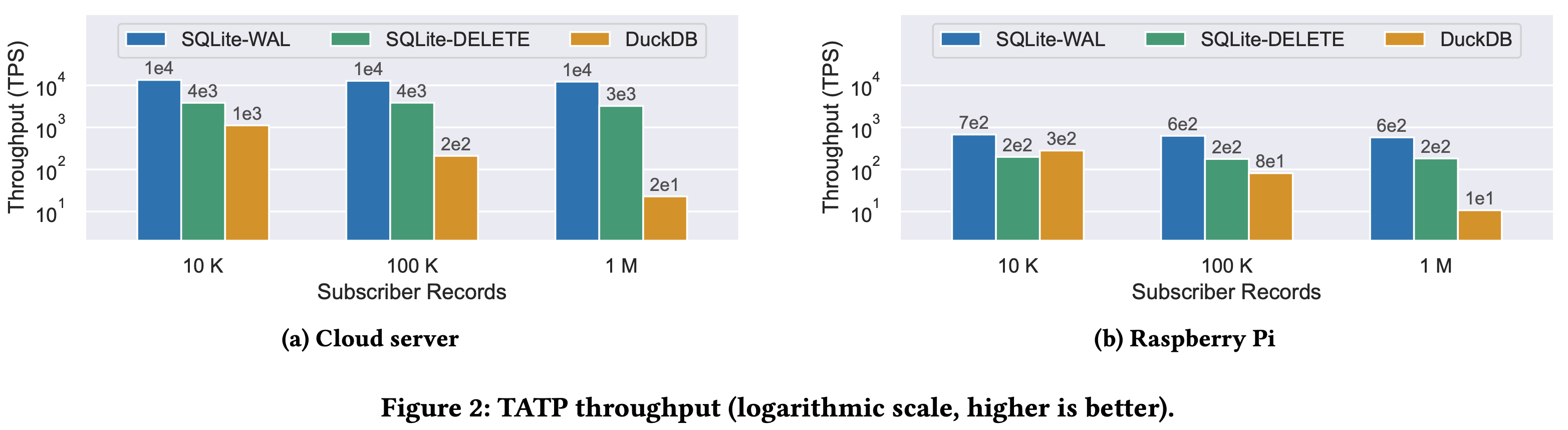

The evaluation section employs three benchmark, to simulate OLTP, OLAP, and blob I/O. The experiments use two hardware configurations: a cloud server, provisioned on CloudLab, with an Intel Xeon Silver 4114 CPU; and a Raspberry Pi 4 Model B with an ARM Cortex-A72 CPU. Both SQLite3 and DuckDB are allowed 1 GB of memory.To evaluate OLTP performance, they use the TATP benchmark. The benchmark consists of seven transaction types that are randomly generated according to fixed probabilities; 80% are read-only, and 20% involve updates, inserts, or deletes. On both hardware configurations, SQLite-WAL produces the highest throughput by a wide margin. On the cloud server, SQLite-WAL reaches a throughput of 10 thousand TPS, which is 10X faster than DuckDB for the small database and 500X faster for the large database.

To evaluate OLAP performance, they use the Star Schema Benchmark (SSB). SSB measures the performance of a database system in a typical data warehousing application. The benchmark uses a modified TPC-H schema that consists of large fact table and four smaller dimension tables. SSB queries involve joins between the fact table and the dimension tables with filters on dimension table attributes. Here for all queries, DuckDB is substantially faster than SQLite. The widest performance margin is on query flight 2, for which DuckDB is 30-50X faster, and the narrowest margin is on flight 1, for which DuckDB is 3-8X faster. SQLite's latency is highly variable across different query flights.

Profiling of SQLite on SSB OLAP workload revealed that only two instructions are responsible for the vast majority of cycles: SeekRowid and Column. The Column instruction extracts a column from a given record. While the Column instruction consumes a substantial amount of cycles for each query, the SeekRowid instruction is largely responsible for the dramatic differences in performance on query flight 1 and query flight 2. The SeekRowid instruction searches a B-tree index for a row with a given row-ID / primary key. When running SSB, SQLite uses the SeekRowid instruction to perform an index join between the fact table and a dimension table. So they identified avoiding unnecessary B-tree probes during joins as a key optimization target.

SQLite uses nested loops to compute joins. The inner loops in the join are typically accelerated with existing primary key indexes or temporary indexes built on the fly. The outer table refers to the table that is scanned in the outermost loop, where as, the inner table refers to the table that is searched, via scan or index, for tuples that join with those in the outer table. They considered two potential optimizations: hash joins and Bloom filters. Hash joins have best-case linear time complexity, however, they often require a significant amount of memory and may spill to storage if the available memory is exhausted. Moreover, adding a second join algorithm to SQLite would considerably increase the complexity of its query planner. In contrast, Bloom filters are memory-efficient and require minimal modification to the query planner. Bloom filters are very powerful for selective star joins, such as those in SSB. For these reasons, they integrated Bloom filters into SQLite's join algorithm.

More specifically, they use Bloom filters to implement Lookahead Information Passing (LIP). LIP optimizes a pipeline of join operators by creating Bloom filters on all the inner (dimension) tables before the join processing starts, and then passing the Bloom filters to the first join operation. The join processing probes the Bloom filters before carrying out the rest of the join. Applying the Bloom filters early in the join pipeline dramatically reduces the number of tuples that flow through the join pipeline, and improves performance. LIP has the advantage of being robust to poor choices of join order.

To implement LIP in SQLite, they add two new virtual instructions to the VDBE: FilterAdd and Filter. FilterAdd computes a hash on an operand and sets the corresponding bit in the Bloom filter. Using the same hash function, Filter computes a hash on an operand and checks the corresponding bit in the Bloom filter. If the bit is unset, the VDBE jumps to a specified address in the bytecode program. When compiling the bytecode program, the query planner initially places each Bloom filter check immediately before the corresponding search of the inner table. If there are multiple Bloom filters, e.g., when three or more tables are joined, SQLite pushes all Bloom filter checks to the beginning of the outer table loop. As a result, SQLite will check all Bloom filters prior to searching the inner tables.

The performance impact of our optimizations is shown in Figure 6. On the Raspberry Pi, SQLite is now 4.2X faster on SSB. Our optimizations are particularly effective for query flight 2, result- ing in 10X speedup. On the cloud server, we observed an overall speedup of 2.7X and individual query speedups up to 7X. The changes cause no appreciable performance degradation elsewhere. The performance profiles in Figure 4 further illustrates the benefits of the Bloom filter (note the difference in scale between Figure 4b and Figure 4a).

As the final section in the experiments, they show an evaluation of blob read/writes. Many applications use SQLite simply as a blob data store. In contrast to basic file manipulation functions such as fwrite, SQLite offers attractive transactional guarantees. In some cases, SQLite reads and writes blob data 35% faster and uses 20% less storage space than the filesystem.

Future

This paper gave a nice overview of SQLite, with emphasis on improvements to OLAP peformance. (If you want to hear --or skim from the transcript-- the human story behind creation and proliferation of SQLite, I found this podcast episode to be excellent.)SQLite is a general-purpose database engine, therefore while extending SQLite's performance for OLAP, they had to hold back to ensure that the modifications cause no significant performance regression across the broad range of workloads served by SQLite, and that they do not break backwards compatibility with previous versions. For example, they considered several means of improving value extraction (obtaining the value of a specific row and column in a table, related to the Column instruction caught in the profiling), but no single solution satisfied the constraints above. Changing the data format from row-oriented to column-oriented would streamline value extraction, but it would also likely increase overhead for OLTP workloads. Moreover, drastic changes to the data format are at odds with SQLite’s goal of stability for the database file format.

In order not to reduce SQLite performance on general OLTP workload, an alternative approach to improving SQLite's OLAP performance is a separate, yet tightly connected query engine that evaluates analytical queries on its own copy of the data, while SQLite continues to serve transactional requests, ensuring that the analytical engine stays up to date with the freshest data. If the extra space overhead is acceptable, the specialized analytical engine can provide substantial OLAP performance gains. This design has been successfully implemented in SQLite3/HE, a query acceleration path for analytics in SQLite (CIDR 22). SQLite3/HE achieves speedups of over 100X on SSB with no degradation in OLTP performance. However, the current implementation of SQLite3/HE does not persist columnar data to storage and is designed to be used in a single process.

I will close by providing perspective and a big picture view. SQLite is an awesome little engine; it reaps the benefits of its size and deployment constraints (single node and mostly single threaded) to keep things simple, agile, and reliable. It is a great motorcycle, but the world also needs fleets of vans and 16-wheelers for high performance scale-out workloads.

MAD Questions

1. Does adding OLAP support make a DB into a HTAP DB?

2. What does HTAP workload look like? Is it just OLTP workload + OLAP workload?

3. Is there a sweet point in design of a database (or a distributed database) for hitting peak HTAP performance?

4. Is it possible to mimic the embedded nature of SQLite in a distributed database?

5. Does testing/profiling also help distributed databases for development velocity?

Yeah, for sure. But is the extent severely limited by the challenges of distribution. Going to distributed implementations, there will be a test-case explosion, and testing may not be as effective as coverage will be sparse. Profiling also gets very difficult and noisy in a distributed deployment.

Comments