Research and climbing

How do you solve a truly hard problem? My undergrad math advisor said it's bit like trying to climb a mountain. You circle and look for a path to the peak that no one else has noticed. Often the searcher with most time and patience wins. Genius isn't what it appears from afar— Bharath Ramsundar (@rbhar90) May 1, 2018

I first liked this. But then I grew uneasy and even disturbed by it... I have been in this business (the research business ---not the climbing) for 20 years, and I find that unfortunately reality is not that simple, idealistic, and egalitarian.

Climbing a mountain is hard and resource intensive

To climb a mountain, you need more than a vision of a feasible path.Last year, I had read this book titled "After the summit" by Lei Wang. It gives life lessons learned from Lei's arduous journey to climb the highest peak on all seven continents, including Mount Everest, and skiing to the North and South poles.

Here is what you need to climb a tough mountain. I think this is still an incomplete list but it is much more than "time and patience" and a "vision of a path to the peak".

- Equipment... very expensive high-quality equipment... good tools are important

- Funding (Just Google for "What do you need to climb everest?". The first link says an Everest climb starts from $35K.)

- Lots of training to get very fit

- Lots of lessons to learn climbing technique

- Training with personal coaches

- Guidance from experts

- A very capable team

- A base camp, where you spend weeks to acclimate

- Experienced sherpas

- Experience of having climbed similar mountains

- Dedication, passion, perseverance

- Managing your mental state

Here are the not so glorious parts about climbing a mountain. You sacrifice a lot. You get your ass kicked by nature, you get your knuckles frozen. You need to learn to walk with spiked boots, you learn to build ladder bridges to walk over wide and deep Crevasses. You learn to sleep out in the cold, eat shitty food. You learn discipline and safety processes. You make discomfort your companion. You learn to tolerate misery.

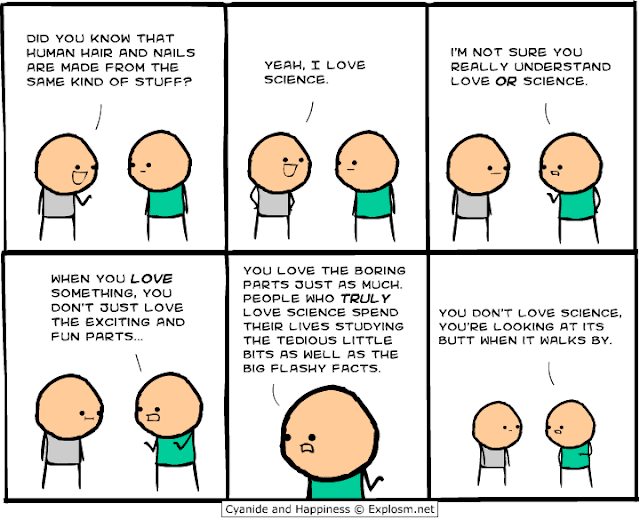

None of this sounds enticing. But probably the worse part is how boring 99% of the climb is. You are at the summit only for 15 minutes. You have to find a way to love the journey.

Just in case this is still unclear, what I wrote for climbing above maps to research one to one, and the mapping is left as an exercise to the reader.

One thing that is not in the climbing task-list is the need for documentation. Maybe documentation is also important for climbers---I don't know, but documentation/writing/publishing is a vital part of research. You need to show the path to others, so that they can see the result, follow-along, and hopefully even improve on it.

MAD questions

1. Man, why am I always so critical?

I think the climbing analogy is actually a good one for research, but I grew unhappy about the emphasis on a very small part of the climbing: "looking for a path that nobody has noticed before". Being the cynic I am, I just had to write this long piece about it. I think I have severe professional deformation: I can't stop finding problems with things.2. Ok, what about Math theorems?

For climbing steep cliffs in theoretical math, is time, patience, and a vision of a path to the peak enough?The theoretical math domain is less resource intensive. But to get an important contribution you still need years of training and years of thinking about the problem in your head. Maybe take off the first items 1 and 2 in my list above and compensate for them with some increased effort in the remaining items. It seems like the mathematicians need to develop and master a lot of mental tools indeed:

Here is the Wikipedia article on Wiles' solution of Fermat's last theorem.

Here is a New Yorker article on Yitang Zhang's work on bounds gaps.

Here is the Wikipedia article on Grigori Perelman's on soul theorem.

3. What are some other analogies you know for the research process?

I like analogies. I wrote this about analogies earlier:It is not hard to make analogies, because all analogies are to some extent inaccurate. When Paul Graham made the analogy about hackers and painters, many people criticized and said that there are many other hackers and vocation analogies. But analogies, while inaccurate, can also be useful. Analogies can give you a new perspective, and can help you translate things from one domain to the other to check if it is possible to learn something from that.I had given research and sudoku analogy before. I still think that is a good analogy. I will leave it to someone else to analyze/criticize that one.

If you have more analogies, please share them with me in the comments.

4. What are some books/articles that got this right?

I recently wrote about the Crypto book. I think it reflected the ups and downs and valleys of death for the discovery process well. I also liked Einstein's biography by Walter Isaacson; it provided a good account of Einstein's work habits and struggles. Although not a book on research, the "War of Art" book by Steven Pressfield did a good job describing the struggles and challenges of creative work. I guess the Dip book by Seth Godin also has relevance.But I want a book that delves more in to the most boring parts of this process. I had heard about (HT @tedherman) biologists spending years perfecting experiments on rats to make sure it is properly designed and free from uncontrolled factors (do check page 35, wow!). I want to read a long book about the boring laborious parts of research.

5. Should we be more cynical?

I said you need a lot of resources to climb a new mountain, but I left it at that. I didn't elaborate on the implications of this for the way research is done.A couple years ago I had read the book "Big Science: Ernest Lawrence and the Invention that Launched the Military-Industrial Complex". Since the 1930s, the scale of scientific endeavor has grown exponentially. Increasingly more, we started to need big teams, big equipment, and big funding for inventions. As the problems get more tricky and more specialized, it is inevitable that the research gets more resource intensive.

Is it a losing battle to try to keep things more egalitarian, keep research more democratized? Yes, research is hard, but if one is very dedicated, work boring hours, do boring work to train, learn the techniques, is it at all possible for her to climb the really tall mountains?

I think the answer is yes.

When we find that we need increasingly more expensive/specialized resources to enter an area, this is an indication that the area has incurred a lot of technical debt. Fortunately, there is a catch up process, where the equipment becomes more affordable (e.g., cloud computing, crispr, 3d printers), and the esoteric techniques are simplified/explained and tooling is provided (e.g., machine learning).

So I am hopeful that it is possible to keep research more democratized. It is also a duty for us to strive for this, otherwise it is an indication we are incurring technical debt in our research field. Researchers are not fond of doing this kind of janitorial stuff and cleaning up, but that is the only way to move forward in a sustainable manner.

Another great equalizer is the emergence of new problems and domains. Innovation begets innovation. As we discover things, we find new terrains open up. And a new terrain is a good opportunity to make impacts without needing immense resources. This is what I had wrote earlier:

We are all equally stupid. Our brains consist of 1.3 kg (3pounds) of gooey material. It is hard to hold 10 variables in our brains simultaneously. Our brains are very poor at reasoning about even very short concurrent programs (I know from first-hand experience :-). Our brains are also very susceptible to biases and fallacies.

The people you see as experts/geniuses are that way because they have been working/thinking/internalizing these topics for more than a decade. Those experts become baffled if you ask them a question a little bit outside of the frame they are accustomed to.

So here is the trick, "you can level the playing field by working on new things/technologies".

Comments